When “GitHub Had A Bad Day” Becomes Your Problem

In mid-November, many teams experienced git push and pull operations failing, even though the GitHub website itself loaded mostly fine. For developers, that translated into broken CI pipelines, stuck deployments, and confused incident channels where nothing in their systems had changed, yet every build was red.

This was not an isolated surprise. GitHub’s own October availability report lists multiple incidents: delayed Actions runs, Codespaces failures with error rates peaking near 100%, and outages tied to third‑party dependencies in the container build path. External monitoring data suggest that GitHub experienced more than 100 incidents in 2024, with Actions, Codespaces, Issues, and other components repeatedly disrupted.

The pattern is clear: outages are no longer rare “acts of God”; they are a regular part of the operating environment for teams whose entire SDLC runs through a small set of third-party SaaS platforms.

Your Platform Engineering Is Only As Good As GitHub’s Worst Week

The uncomfortable truth is that many “elite” engineering organizations have quietly built a single-vendor backbone: GitHub for source, review, CI, and artifacts; one or two clouds for everything else. When that backbone has a bad week, DORA metrics and incident charts look indistinguishable from internal process failure, even when the root cause lives entirely outside the org.

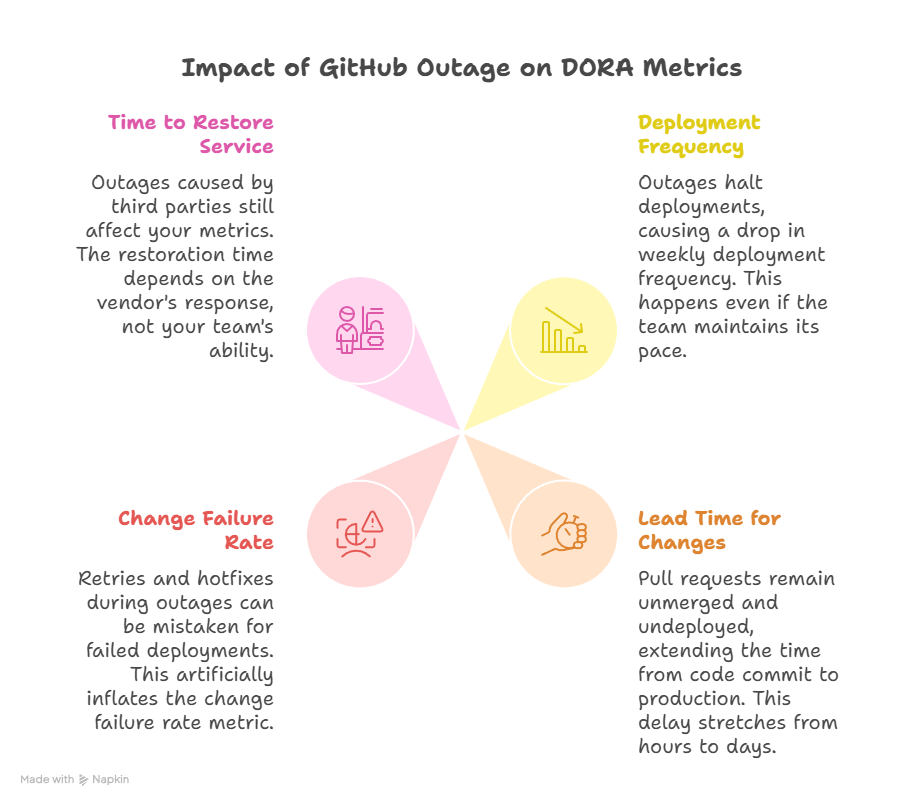

Consider what a GitHub outage does to each DORA metric:

On‑call engineers feel this first. Instead of investigating a known component, they are reduced to refreshing status pages, scanning Reddit, and then writing half‑hearted incident updates that say, “waiting on GitHub.” Over time, this corrodes trust in both the tooling and the metrics used to judge engineering performance.

Designing For Graceful Degradation, Not Heroic Recovery

Outages are inevitable; fragility is optional. Resilient teams deliberately design workflows that degrade gracefully when Git or CI is down instead of treating platform outages as unmodelled chaos. That usually means attacking three failure modes: “I can’t move code,” “I can’t run pipelines,” and “I can’t see what’s happening.”

1. Local mirrors and alternative remotes

Relying on a single Git remote is convenient until it blocks all work. A few pragmatic patterns:

- Maintain a read‑only mirror of critical repositories in a separate system (self‑hosted Git, another provider, or cloud‑native code hosting).

- For core services, support dual remotes in docs: origin on GitHub, backup on an internal mirror which can serve as a temporary upstream for hotfixes.

- Periodically test the escape hatch: can you cut a release from the mirror, tag it, and reconcile later when GitHub is back?

This does not remove GitHub from the loop, but it prevents total paralysis when pushes and pulls to the primary remote are blocked.

2. Read‑only, “offline‑friendly” workflows

If GitHub’s UI or API is flaky, a surprising amount of productive work can still happen if your practices allow it.

- Encourage local review and pairing: engineers can continue reviewing diffs locally and capturing notes to apply once the PR system is back.

- Adopt feature flags and decoupled releases so you are not forced into emergency deploys during an outage window.

- For critical operations, define manual, paper‑clip runbooks: how to build, test, and deploy from a developer machine or a separate CI when the main pipeline is unavailable.

The goal is to avoid a binary mode of “CI up = work; CI down = we all stare at Slack.”

3. Failing safely in CI/CD

CI outages often convert into risky manual deploys, which then inflate the change failure rate and time‑to‑restore when something goes wrong. Resilient pipelines are explicit about what is allowed when the primary system is degraded. For example:

- Permit only rollback or config‑toggle deploys via a secondary mechanism (e.g., an internal script or alternate pipeline) during vendor incidents.

- Require an incident ID and approval for any deployment during known third‑party outages, so they are visible in post‑incident analysis.

- Tag all such deployments so DORA queries can distinguish “incident mitigation” from normal releases.

This keeps the system safer and makes the metrics more honest.

Making Vendor Outages Visible In Metrics

If everything runs through GitHub and your dashboards don’t distinguish internal vs external causes, your DORA metrics will punish teams for someone else’s uptime. Instrumentation is part technical, part sociotechnical:

- Tag incidents by source. When you open an incident in your tracker, add a label like

source=vendor/githuborsource=cloudflare, so stability metrics can be sliced later. - Enrich DORA queries with incident data. Instead of deriving the change failure rate purely from pipeline states, join with your incident system so failures caused by external outages are explicitly visible.

- Annotate dashboards with status‑page events. Pull in data from vendor status APIs or RSS feeds and show incident windows on your velocity and stability charts.

The objective is not to excuse everything as “GitHub’s fault,” but to create an honest picture of what your team actually controls.

How To Talk About This With Execs And Boards

From a leadership perspective, GitHub and similar platforms are line items on a bill, not existential dependencies until a bad week surfaces that risk. The conversation needs to move from “GitHub was down again” to “here’s how external dependencies factor into our resilience and performance profile.”

A useful framing for non‑technical stakeholders:

- Clarify ownership boundaries. Explain which parts of the SDLC are in your control (code quality, pipeline design, on‑call response) and which sit with vendors (git availability, hosted runners, status of external clouds).

- Show impact with annotated metrics. Present DORA trends with vendor‑incident overlays: “Deployment frequency dropped by 40% during these three days; these coincide with GitHub Actions and Codespaces outages.”

- Propose specific resilience investments. Instead of venting, walk in with a checklist: funding a mirror, adding observability to CI, formalizing incident tagging, and establishing a policy for secondary deploy paths.

- Align on risk appetite. Some organizations will accept occasional downtime in exchange for the leverage GitHub provides; others, especially in regulated or high‑availability domains, may decide to diversify providers or bring critical paths in‑house.

Framed this way, a GitHub‑heavy stack becomes a conscious strategic choice, with explicit mitigations and reporting, rather than an unexamined default.

Turning “Worst Week” Into A Design Constraint

The right mental model is not “How do we avoid GitHub ever going down?” but “How much of our business should stall when GitHub has its worst week of the year?” The answer to that question drives architecture, process, and even budgeting decisions.

For engineering managers and platform teams, this is an opportunity. Every outage thread in chat, every frustrated screenshot of a failing git push, is raw data you can convert into a resilience roadmap, cleaner metrics, and more honest conversations about the real shape of “reliable engineering” in a SaaS‑dependent world.